Section 1: The Nature of Addiction: A Chronic Medical Condition

Understanding the journey to recovery begins with a clear, evidence-based understanding of addiction itself. For decades, addiction was shrouded in moral judgment and misconceptions, often viewed as a character flaw or a failure of willpower. Modern science and medicine have definitively overturned these outdated notions, recasting addiction as a complex but treatable medical condition. This foundational understanding is not merely academic; it is the first and most crucial step toward dismantling the shame and stigma that prevent so many from seeking help. By framing addiction within a medical model, we can approach it with the same compassion, scientific rigor, and hope that we apply to other chronic diseases.

1.1 Defining Addiction: The Medical Consensus

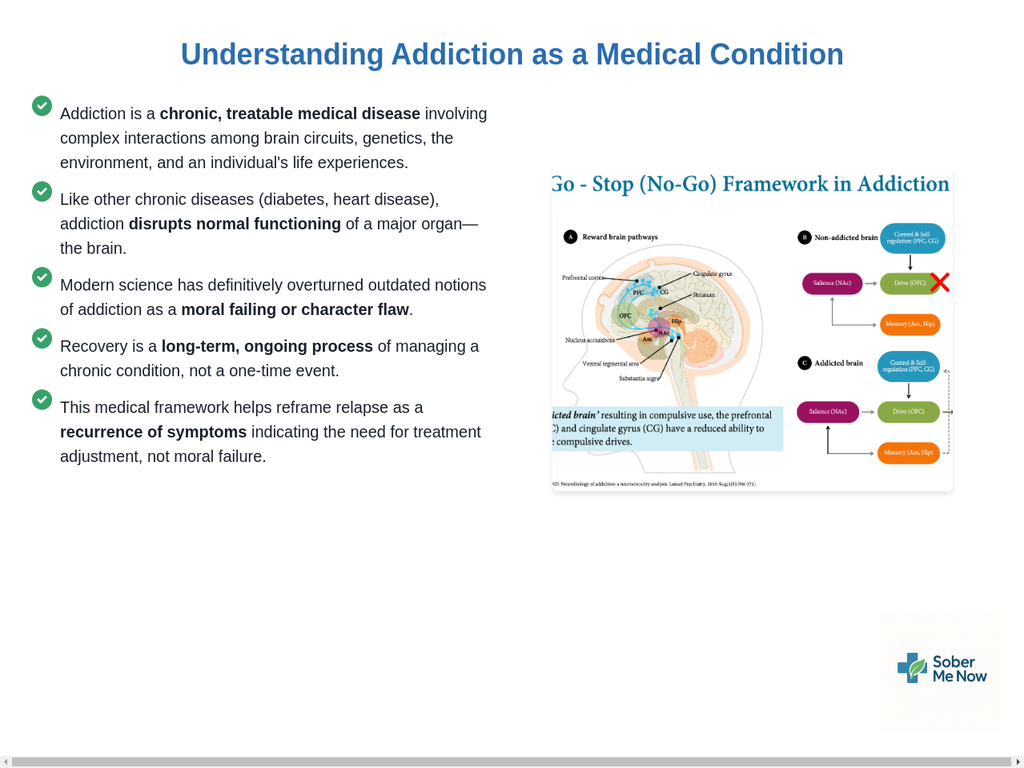

Leading medical organizations have established clear, concise definitions that anchor our understanding of addiction in science. The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) defines addiction as a “treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual’s life experiences”. This definition highlights that people with addiction use substances or engage in behaviors that become compulsive and often continue despite harmful consequences. Similarly, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) defines addiction as a “chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences”.

The consistent use of terms like “chronic” and “relapsing” by these authorities is profoundly significant. It positions addiction alongside other chronic illnesses such as heart disease, asthma, and diabetes. This comparison is not just an analogy; it is a clinical reality. Like these other conditions, addiction disrupts the normal, healthy functioning of a major organ—the brain. It has serious, harmful effects, and while it is often preventable and treatable, it can last a lifetime and may lead to death if left untreated.

This medical framework has powerful implications for how individuals and society should view recovery. If addiction is a chronic disease, then its management is a long-term, ongoing process, not a one-time event. A person with diabetes does not attend a 30-day program and consider themselves “cured”; they engage in a lifetime of management involving medication, diet, exercise, and regular check-ups. Similarly, recovery from addiction is a sustained journey of managing a chronic condition. This perspective helps to reframe relapse not as a moral failure or a sign that treatment has failed, but as a potential recurrence of symptoms, indicating that the management plan needs to be reviewed and adjusted. This shift in perspective can alleviate immense guilt and shame, encouraging individuals to re-engage with treatment rather than hide in despair.

1.2 The Addicted Brain: How Hijacking Happens

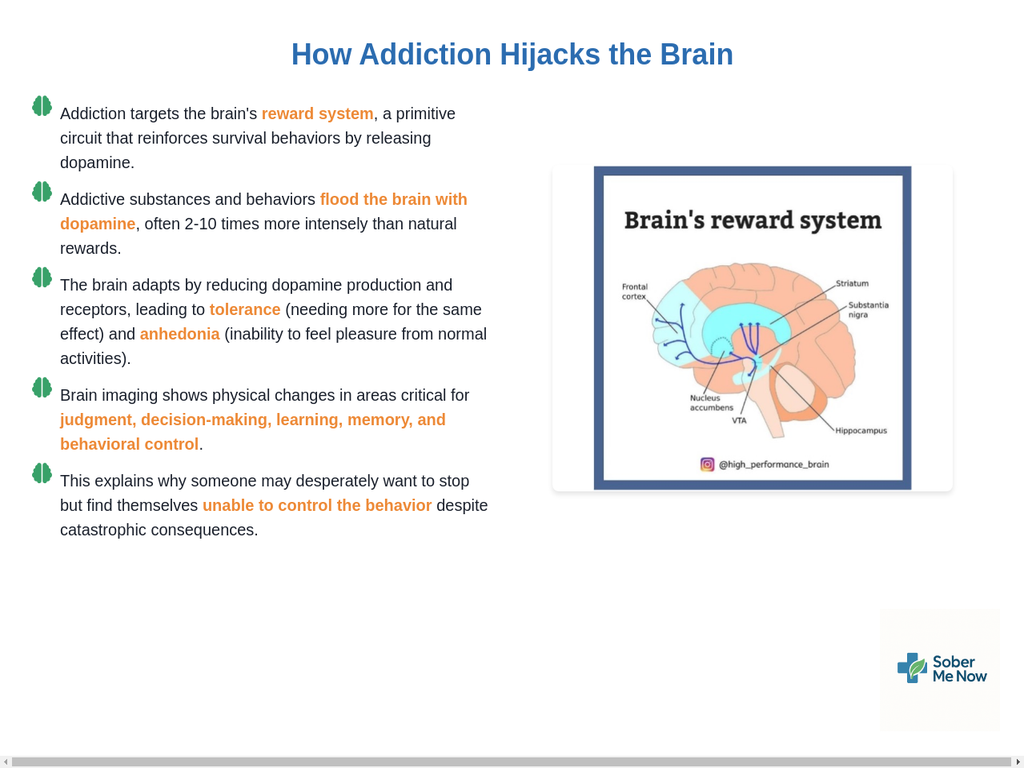

The compulsive, often baffling behaviors associated with addiction are not a matter of choice; they are the direct result of profound and lasting changes in the brain’s structure and function. At the heart of this process is the brain’s reward system, a primitive circuit essential for survival that reinforces life-sustaining behaviors like eating and procreating by releasing a neurotransmitter called dopamine. This release of dopamine creates feelings of pleasure and “teaches” the brain to repeat the behavior that caused it.

Nearly all addictive substances and behaviors hijack this system by flooding it with dopamine, often far more intensely and reliably than natural rewards. This massive overstimulation creates a powerful reinforcing signal that leads to compulsive drug seeking and use. The brain begins to adapt to this constant overstimulation in several ways. It may reduce its own dopamine production or decrease the number of dopamine receptors in the reward circuit. As a result, the person’s ability to experience pleasure from once-enjoyable activities (like food or socializing) diminishes. This state, known as anhedonia, is a hallmark of addiction. The substance or behavior is no longer sought for euphoria but simply to feel “normal” and to alleviate the distress of its absence.

Crucially, these changes extend beyond the reward circuit. Brain imaging studies of people with addiction reveal physical and functional alterations in areas of the brain critical for judgment, decision-making, learning, memory, and, most importantly, behavioral control. The prefrontal cortex, the brain’s “executive” center responsible for inhibiting impulses and assessing consequences, becomes compromised. This impairment in self-control is the very essence of addiction. It explains why an individual may desperately want to stop but find themselves unable to do so, despite catastrophic consequences to their health, relationships, and finances.

This neurobiological reality also explains why different therapeutic approaches can be effective. The brain’s impaired executive function is the core problem. Some recovery models, like 12-Step programs, effectively address this by having the individual “surrender” and outsource this compromised control to an external structure—the program and a “higher power”. Other models, like those based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, work to directly retrain and strengthen these impaired brain circuits, helping the individual rebuild their internal locus of control. These seemingly opposite philosophies are, in fact, addressing the same neurobiological deficit from two different, valid perspectives.

1.3 Substance vs. Behavioral Addictions: Different Paths, Same Destination

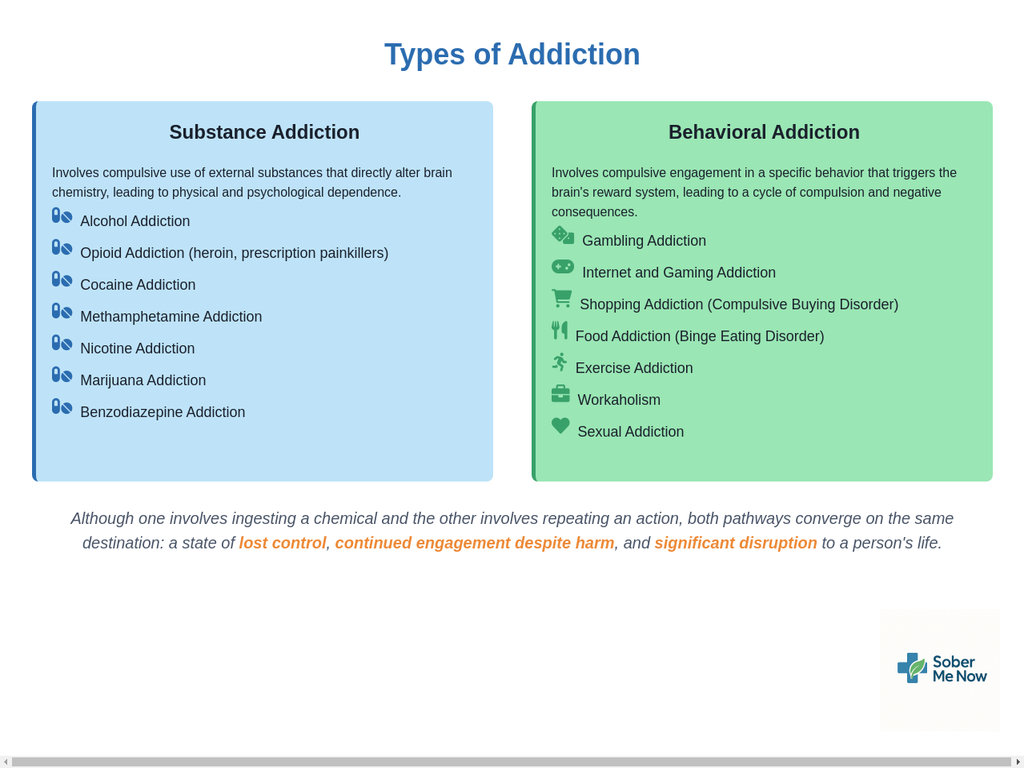

Addiction can manifest in two primary forms: substance addiction and behavioral addiction. While the specific mechanisms differ, the underlying neurobiology and the resulting pattern of compulsive behavior are remarkably similar.

Substance Addiction, also referred to as a substance use disorder (SUD), involves the compulsive use of external substances that directly alter brain chemistry, leading to physical and psychological dependence. Examples are wide-ranging and include:

- Alcohol Addiction

- Opioid Addiction (heroin, prescription painkillers)

- Cocaine Addiction

- Methamphetamine Addiction

- Nicotine Addiction

- Marijuana Addiction

- Benzodiazepine Addiction

Behavioral Addiction, also known as process addiction, involves compulsive engagement in a specific behavior that does not involve an external psychoactive substance. The behavior itself—the “process”—triggers the brain’s reward system, leading to a cycle of compulsion and negative consequences. These addictions are increasingly recognized by the medical community and can be just as devastating as substance addictions. Examples include:

- Gambling Addiction

- Internet and Gaming Addiction

- Shopping Addiction (Compulsive Buying Disorder)

- Food Addiction (Binge Eating Disorder)

- Exercise Addiction

- Workaholism

- Sexual Addiction

- Social Media Addiction

Although one involves ingesting a chemical and the other involves repeating an action, both pathways converge on the same destination: a state of lost control, continued engagement despite harm, and significant disruption to a person’s life. Recognizing the validity of behavioral addictions is crucial for validating the suffering of those who struggle with them and ensuring they receive appropriate, specialized help.

1.4 Recognizing the Signs: From Behavioral Shifts to Physical Symptoms

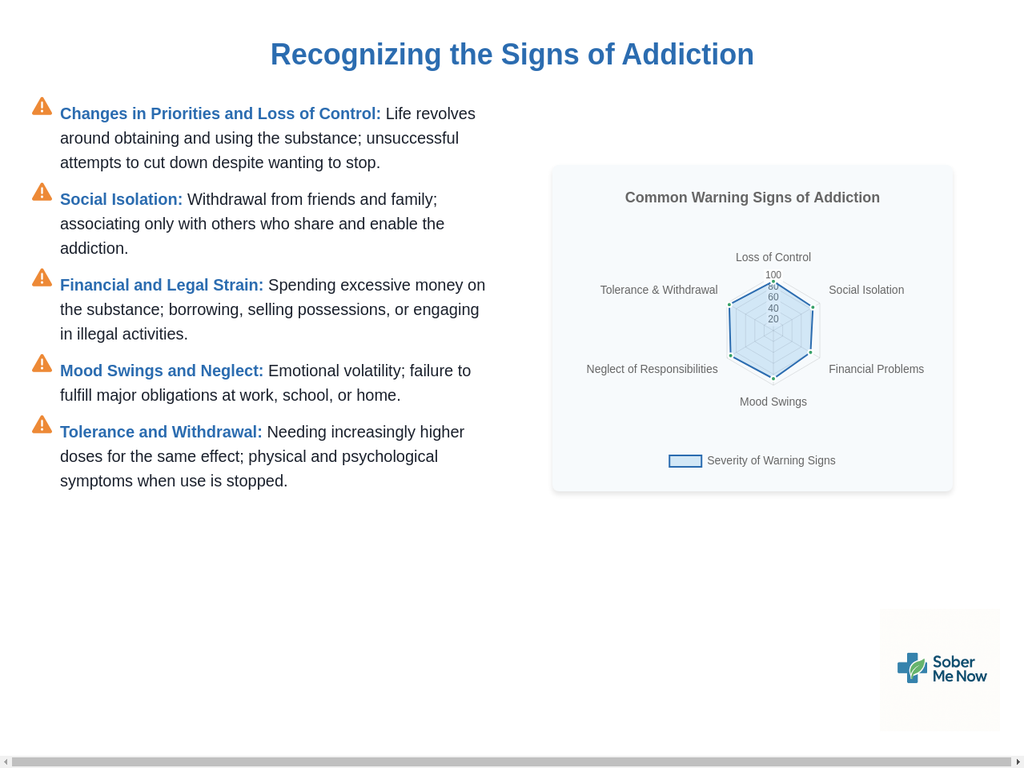

Translating the clinical definition of addiction into real-world terms involves recognizing a pattern of characteristic signs and symptoms. While these can vary based on the specific substance or behavior, a common constellation of indicators often emerges. These signs provide a concrete tool for self-assessment or for families to identify when a loved one may need help.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a diagnosis of a substance use disorder is based on a pattern of behaviors that cause significant impairment or distress. Key behavioral, psychological, and physical signs include:

- Changes in Priorities and Loss of Control: This is often the first and most noticeable sign. Hobbies, relationships, work, and other responsibilities become less important as the individual’s life begins to revolve around obtaining and using the substance or engaging in the behavior. They may take the substance in larger amounts or for longer than intended and have a persistent desire, coupled with unsuccessful efforts, to cut down or stop.

- Social Isolation: Individuals with addiction often withdraw from friends and family. This can be a defense mechanism to avoid judgment, hide the extent of their behavior, or to associate only with others who share and enable the addiction.

- Financial and Legal Strain: Addiction can be an expensive habit. Financial problems may arise from spending excessive money on the substance or behavior, leading to borrowing, selling possessions, or engaging in illegal activities to fund the addiction. This can result in legal issues, such as arrests for theft or driving under the influence.

- Drastic Mood Swings: A common indicator is emotional volatility. The individual may experience euphoria or a sense of power while using, followed by extreme irritability, anxiety, or depression when they are not.

- Neglect of Responsibilities: The compulsion to use leads to a failure to fulfill major obligations at work, school, or home. This can manifest as poor performance, absenteeism, or neglect of family duties.

- Risk-Taking Behavior: An individual may continue to use in situations where it is physically hazardous, such as driving while impaired.

- Tolerance and Withdrawal: Tolerance is the need to take increasingly higher doses of a drug to achieve the same effect. Physical dependence occurs when the body adapts to the substance, and withdrawal symptoms emerge when use is stopped. These symptoms can be both physical (e.g., shaking, nausea) and psychological (e.g., anxiety, depression), and the person may continue using simply to avoid them.

Recognizing these signs is not about placing blame but about identifying a treatable medical condition that requires professional intervention.

Section 2: The Recovery Trajectory: Navigating the Path to Wellness

The journey of recovery is not a straight line but a dynamic process with distinct stages, challenges, and milestones. Understanding this trajectory can demystify the experience, providing a roadmap that helps individuals and their families anticipate hurdles, celebrate progress, and maintain hope. It is a path that moves from acknowledging a problem to actively building a new life, and while it is demanding, it is a well-traveled one with clear guideposts to follow.

2.1 The Stages of Change: Where Are You on the Journey?

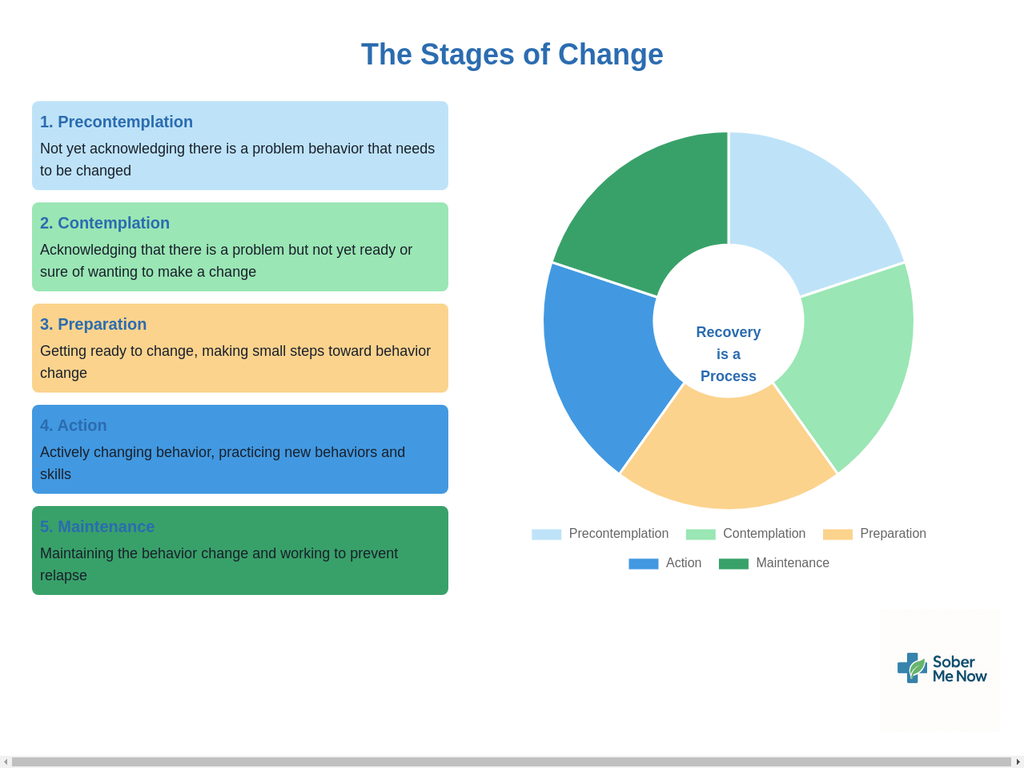

A powerful and non-judgmental framework for understanding the recovery process is the Transtheoretical Model of Change, also known as the Stages of Change model. Developed by researchers Prochaska and DiClemente, this model posits that people move through a series of five distinct stages as they adopt a new, healthy behavior. It normalizes the ambivalence and setbacks that are a natural part of any significant life change.

The five stages are:

- Precontemplation: In this stage, the individual does not see their behavior as a problem and is not considering change. They may be in denial about the negative consequences or rationalize their use, often saying things like, “I can quit anytime I want”. They are often defensive and resistant to outside input.

- Contemplation: Here, the individual becomes aware that their behavior is problematic and begins to consider the pros and cons of changing. However, they are not yet ready to make a firm commitment to action. This stage is characterized by ambivalence; they know they should change but are not ready to do so. People can remain in this stage for long periods.

- Preparation: The individual now has the intent to take action in the near future. They have accepted that their behavior is a problem and are beginning to take small steps, such as researching treatment programs, calling clinics, or making a plan to quit.

- Action: This is the stage where the individual actively modifies their behavior and lifestyle. They are implementing their plan, which may involve entering a treatment program, attending support groups, and stopping the use of substances. This stage requires the most commitment and carries a high risk of relapse as new habits are formed.

- Maintenance: In this final stage, the individual works to sustain the changes made during the action stage and prevent relapse. The goal is to solidify the new behaviors as a permanent part of their life. This stage can last from six months to a lifetime.

This model is not just a descriptive tool; it is a powerful guide for intervention. The support needed for someone in Precontemplation (e.g., gently raising awareness of consequences) is fundamentally different from the support needed for someone in Preparation (e.g., providing concrete treatment options). Trying to force someone in Contemplation into Action is likely to fail because their ambivalence hasn’t been resolved. Instead, a tool like Motivational Interviewing, which is designed to explore and resolve ambivalence, is the appropriate intervention for that stage. By understanding where a person is on this continuum, helpers can “meet them where they are,” dramatically increasing the effectiveness of their support.

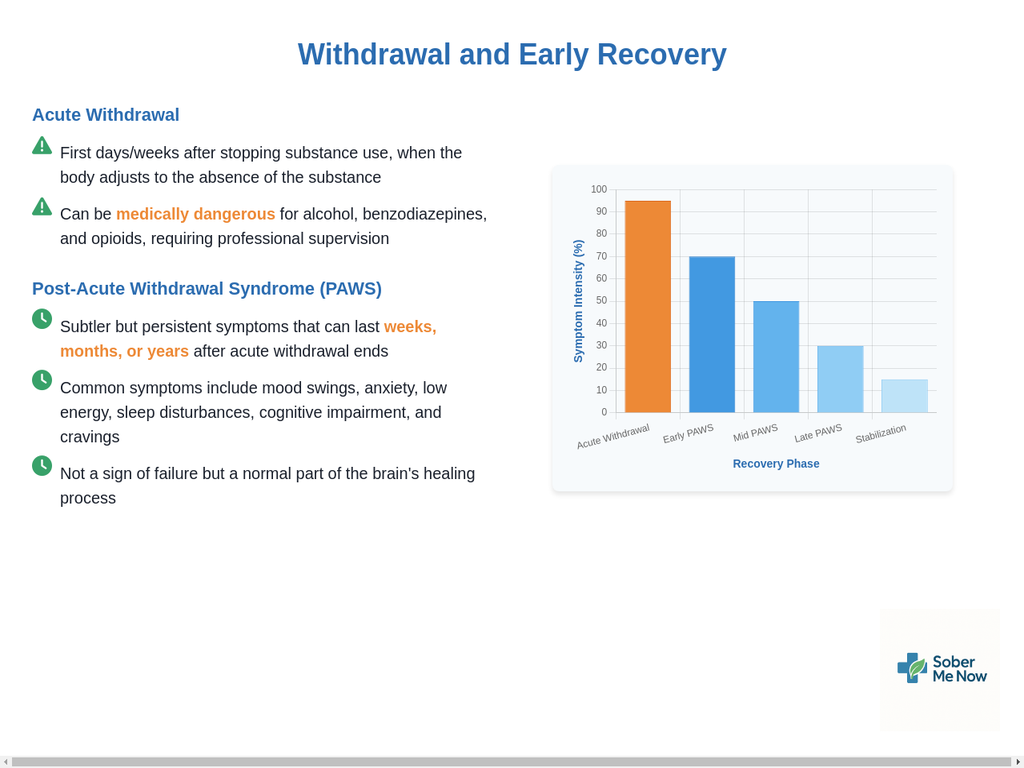

2.2 Acute Withdrawal: The First Hurdle

For those with physical dependence on a substance, the first major obstacle in the Action stage is acute withdrawal. This refers to the set of symptoms that emerge in the first days and weeks after substance use is stopped or drastically reduced. The body and brain, having adapted to the constant presence of the drug, must now readjust to its absence.

The severity and nature of acute withdrawal symptoms vary widely depending on the substance, the duration and frequency of use, and individual health factors. For some substances, withdrawal is primarily psychological and deeply uncomfortable. For others, particularly alcohol, benzodiazepines (e.g., Xanax, Valium), and opioids, withdrawal can be not only severe but also medically dangerous and potentially life-threatening. For this reason, attempting to “go cold turkey” at home is strongly discouraged for these substances. A medically supervised detoxification, often in an inpatient setting, provides 24-hour medical care to manage symptoms safely and make the process as comfortable as possible. This professional oversight can be the difference between a safe start to recovery and a dangerous, unsuccessful attempt.

2.3 Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS): The Hidden Hurdle

Many people believe that once they have endured the intense initial phase of acute withdrawal, the worst is over. However, a less understood but critically important phenomenon often follows: Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome, or PAWS. PAWS is a collection of subtler but persistent and often fluctuating symptoms that can linger for weeks, months, or in some cases, even years after acute withdrawal has ended.

PAWS is not a sign of psychological weakness or a failure of recovery; it is a physiological process. It is the direct result of the brain slowly healing and recalibrating its chemistry and neural pathways after prolonged substance use. The brain’s stress, reward, and sleep-regulating systems, which were thrown into disarray by addiction, are gradually returning to a state of equilibrium.

Common symptoms of PAWS include:

- Mood Swings: Unpredictable shifts between feeling okay and experiencing intense sadness, anger, or anxiety.

- Anxiety and Irritability: Persistent feelings of nervousness, worry, and a lowered threshold for frustration.

- Low Energy and Fatigue: A pervasive sense of exhaustion that is not relieved by rest.

- Sleep Disturbances: Difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or experiencing non-restorative sleep (insomnia).

- Cognitive Impairment: Problems with concentration, memory, and clear thinking, often described as “brain fog”.

- Anhedonia: A diminished ability to feel pleasure from activities that were once enjoyable.

- Cravings: The sudden and intense urge to use the substance.

Understanding PAWS is essential for preventing relapse. When these symptoms appear unexpectedly after a period of feeling well, an individual might mistakenly believe that “sobriety isn’t working” or that they are permanently broken. This despair is a major trigger for returning to substance use. Knowing that PAWS is a normal, temporary, and treatable part of the brain’s healing journey provides immense validation and hope. It redefines the timeline of “early recovery” from a matter of weeks to a period of many months or even a few years, highlighting the absolute necessity of long-term, sustained support to navigate this vulnerable phase successfully.

2.4 Managing Triggers and Cravings: Proactive Strategies for Prevention

A central task of early and long-term recovery is learning to manage triggers and cravings. These are the daily realities that can threaten sobriety if not addressed with a proactive and well-rehearsed plan.

A trigger is any internal or external cue that sparks the thought of using. Triggers are highly personal but often fall into common categories:

- External Triggers: These are people, places, things, or situations in the environment associated with past use. Examples include seeing drug paraphernalia, being around friends who are still using, driving past a specific bar, or even experiencing holidays or stressful events.

- Internal Triggers: These are thoughts, feelings, or physical sensations that arise from within. Examples include feelings of stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness, boredom, or even abnormally positive emotions (which the brain may associate with a desire to “celebrate” with the substance). Memories of past use can also be powerful internal triggers.

A craving is the intense psychological or physical desire to use a substance that is often sparked by a trigger. Cravings can feel overwhelming, but a key piece of knowledge is that they are temporary and typically short-lived, often peaking and subsiding within a matter of minutes if not acted upon.

Managing these phenomena requires a multi-layered strategy that moves from awareness to action:

- Identify Your Triggers: The first step is to become a detective of your own internal and external landscape. Keeping a journal to log when cravings occur—noting the situation, the feeling, and the thought—can reveal patterns and identify your specific high-risk triggers.

- Avoid and Plan: Once triggers are identified, the simplest strategy is to avoid them when possible. This might mean changing your route to work to avoid a liquor store or declining invitations to events where alcohol is central. For triggers that cannot be avoided, create a detailed plan in advance. For every trigger, brainstorm three different ways you can challenge it, avoid it, or remove yourself from the situation.

- Set Firm Boundaries: Recovery often requires making difficult but necessary changes to your social environment. This means learning to set and enforce healthy personal boundaries, which might include cutting ties with friends who do not support your recovery, being clear with family about not having substances in the house, or avoiding media that glorifies use.

- Challenge Your Thoughts: Cravings are fueled by intrusive thoughts. A core skill is to learn to challenge these thoughts rather than accept them as commands. This involves recognizing the thought (“A drink would make me feel better”), questioning its validity (“Will it really? Or will it make things worse in an hour?”), and replacing it with a positive, recovery-focused thought (“I am choosing health and I have other ways to cope with this stress”).

- Ride the Wave: Utilize mindfulness techniques to “urge surf.” Instead of fighting a craving, you observe it without judgment, acknowledging its presence and recognizing that it is a temporary wave of sensation that will crest and pass on its own. Leaning into self-care and reminding yourself of your long-term goals can help you navigate these intense but fleeting moments.

By developing and practicing these skills, individuals move from being reactive victims of their triggers to proactive architects of their recovery.

Section 3: Clinical Interventions: The Foundation of Formal Treatment

While peer support and personal lifestyle changes are vital, the foundation of a robust recovery plan is often built upon clinical interventions. Formal treatment, guided by medical and therapeutic professionals, provides the evidence-based tools, medical stability, and structured environment necessary to address the deep-seated biological, psychological, and social dimensions of addiction. Navigating the world of treatment can be daunting, but understanding the different levels of care and the core therapeutic modalities empowers individuals to become informed and active participants in their own healing journey.

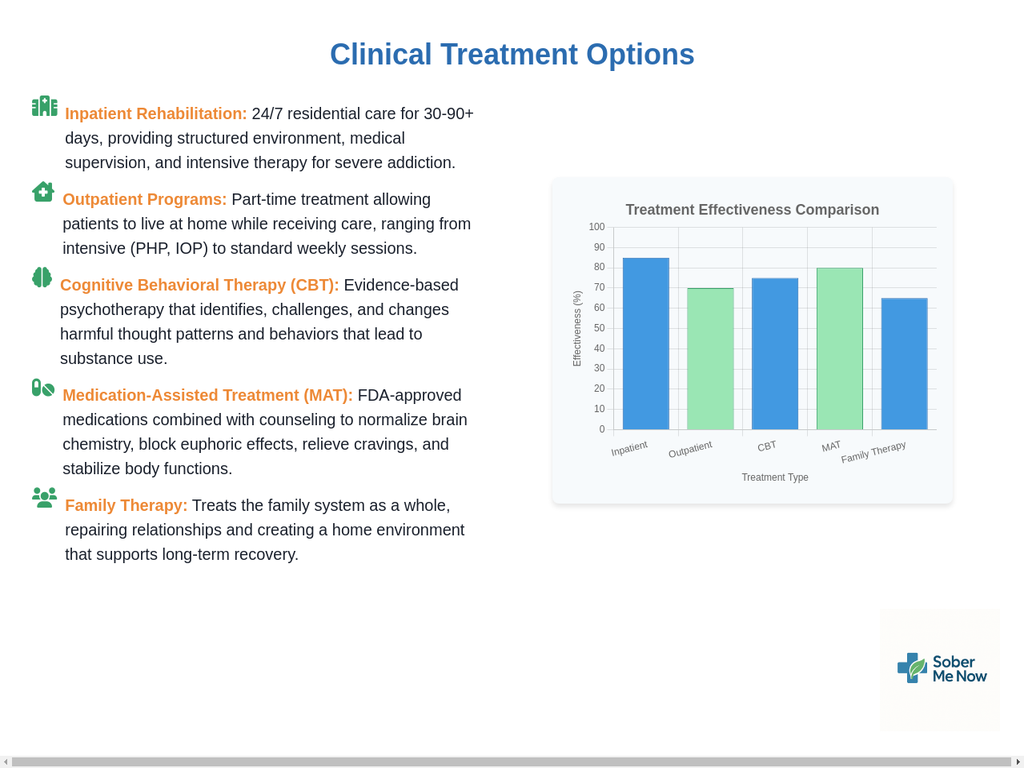

3.1 Levels of Care: Inpatient vs. Outpatient Programs

Addiction treatment is not a one-size-fits-all process. It is delivered across a continuum of care, allowing for treatment plans to be matched to the severity of the disorder and the individual’s specific needs. The two primary settings are inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation.

Inpatient Rehabilitation, also known as residential treatment, is the most intensive level of care. It requires the individual to live at the treatment facility for a set period, typically ranging from 30 to 90 days or longer. This controlled, 24/7 environment removes the person from external triggers and allows for a singular focus on recovery. Inpatient care is generally recommended for individuals with:

- Serious or severe substance use disorders.

- A need for medically supervised detoxification, especially for substances like alcohol or benzodiazepines where withdrawal can be life-threatening.

- Co-occurring medical or psychological conditions that require intensive monitoring.

- A living environment that is not conducive to recovery.

To be admitted to an acute inpatient program, a person must generally be in stable medical condition and be able to tolerate and benefit from several hours of therapy per day.

Outpatient Rehabilitation offers treatment on a part-time basis, allowing the individual to continue living at home and maintain work or school responsibilities. This option is suitable for those with milder substance use disorders or as a “step-down” for individuals who have completed an inpatient program and are transitioning back to their daily lives. Outpatient care exists at several levels of intensity:

- Partial Hospitalization Program (PHP): The most intensive outpatient level, often involving treatment for 5-6 hours per day, 5-6 days a week. It provides a high degree of structure and is often used as a direct alternative to, or transition from, residential care.

- Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP): A step down from PHP, IOP typically involves 3 hours of treatment per day for 3-5 days a week. This allows for more flexibility to reintegrate into work and family life while still receiving substantial support.

- Standard Outpatient: This involves less frequent meetings, perhaps once or twice a week, for individual or group counseling.

The choice between inpatient and outpatient care is a critical one, best made in consultation with a medical or addiction professional who can assess the individual’s unique situation and recommend the appropriate level of care.

3.2 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Rewiring Your Thoughts

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective and widely used evidence-based psychotherapies for addiction. It is a practical, goal-oriented, and action-focused approach that operates on a simple but powerful premise: our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are interconnected, and by changing our patterns of thinking, we can change our behavior.

CBT helps individuals in recovery by teaching them to identify, challenge, and reframe the harmful or irrational thought patterns that lead to substance use. Therapists help patients recognize their negative “automatic thoughts”—the impulsive, often self-defeating beliefs that pop into their minds and trigger cravings. For example, an automatic thought like, “I failed at this task, so I’m worthless and need a drink,” can be systematically dismantled and replaced with a more balanced and rational thought, such as, “I made a mistake, but I can learn from it. I don’t need alcohol to cope with this feeling.”

CBT is not just talk therapy; it is a skills-based training that equips individuals with a toolkit of practical techniques they can use in their daily lives. These techniques include:

- Thought Records: A structured worksheet where individuals log a triggering situation, their automatic thoughts and feelings, the evidence for and against those thoughts, and a more balanced alternative thought.

- Behavioral Experiments: Actively testing the validity of a negative belief. For example, a person who believes they are “too anxious to go to a support meeting” might be encouraged to attend for just 15 minutes as an experiment to see if their catastrophic prediction comes true.

- Pleasant Activity Scheduling: Intentionally scheduling healthy, enjoyable activities into the week to counteract negative moods and break the routine of substance use.

- Imagery Based Exposure: For individuals whose substance use is linked to trauma, this technique involves guided, repeated exposure to painful memories in a safe therapeutic setting to reduce the anxiety and emotional power they hold over time.

A significant advantage of CBT is its efficiency and adaptability. Meaningful results can often be achieved in a relatively short number of sessions (around 16 is common), and its principles can be applied in inpatient, outpatient, individual, and group settings.

3.3 Motivational Interviewing (MI): Finding Your “Why”

While CBT provides the “how” of changing behavior, Motivational Interviewing (MI) often provides the “why.” MI is a collaborative counseling style specifically designed to explore and resolve the ambivalence that keeps people stuck in the contemplation stage of change. It is not about confronting, persuading, or directing the individual; instead, it is about evoking their own intrinsic motivation to change.

The “spirit” of MI is one of partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation. The therapist acts as a guide, not an authority figure, helping the person identify the discrepancy between their current behaviors and their deeply held values and goals. The core of the practice lies in a set of communication skills known by the acronym

OARS:

- Open Questions: Asking questions that cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no,” inviting the person to tell their story (e.g., “What are some of the things you don’t like about your drinking?”).

- Affirmations: Recognizing and acknowledging the person’s strengths, efforts, and past successes to build their confidence (e.g., “It took a lot of courage to even come here today.”).

- Reflective Listening: Carefully listening and reflecting back what the person has said to show that they are being heard and understood. This is the most crucial skill in MI.

- Summarizing: Periodically pulling together the key points of the conversation, especially the person’s own “change talk”—statements that favor making a change.

By skillfully using OARS, the therapist helps the individual articulate their own reasons for change, strengthening their commitment. Studies show that MI is highly effective at increasing engagement and retention in treatment. It is a respectful and empowering approach that honors the individual’s autonomy, making it a powerful tool for building the therapeutic alliance and preparing someone for the hard work of the Action stage.

3.4 Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT): Stabilizing the Brain

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is an evidence-based approach that combines FDA-approved medications with counseling and behavioral therapies to treat substance use disorders, particularly opioid use disorder (OUD) and alcohol use disorder (AUD). It is crucial to combat the stigma that MAT is simply “substituting one drug for another.” In reality, these are life-saving medical treatments that work by normalizing brain chemistry, blocking the euphoric effects of substances, relieving cravings, and normalizing body functions without the negative effects of the abused substance.

By stabilizing the brain, MAT allows the individual to overcome the overwhelming biological compulsion to use, creating the mental and emotional space needed to engage in and benefit from psychosocial therapies like CBT and family counseling. In the context of the opioid crisis, MAT is a cornerstone of harm reduction and overdose prevention. Research shows that people with OUD who are treated with methadone or buprenorphine are 50% less likely to die of an overdose compared to those receiving no treatment. The term Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) is increasingly used to emphasize that these medications are a primary, effective treatment in their own right, not just an “assistant” to therapy.

The three FDA-approved medications for OUD are:

- Methadone: A full opioid agonist that reduces cravings and withdrawal symptoms. It is highly effective but can only be dispensed through federally licensed Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) in daily, supervised doses.

- Buprenorphine: A partial opioid agonist that also controls cravings and withdrawal. It has a lower risk of overdose than methadone and can be prescribed by any qualified clinician in an office-based setting, greatly increasing access to care. It is often combined with naloxone (an opioid blocker) in products like Suboxone to deter misuse.

- Naltrexone: An opioid antagonist that works by blocking the euphoric and sedative effects of opioids. It is not an opioid and is not addictive. However, it can only be started after an individual has been fully detoxed from all opioids for 7-10 days, as it can precipitate severe withdrawal if taken too soon. It is available as a daily pill or a monthly extended-release injection.

3.5 Family Therapy: Healing the System

Addiction is often called a “family disease” because its effects ripple outward, causing stress, dysfunction, and pain for the entire family unit. Consequently, effective treatment often involves healing not just the individual, but the family system itself. Family therapy is a form of psychotherapy that brings family members together to improve communication, resolve conflicts, and learn healthier ways of interacting and supporting recovery.

The focus of family therapy moves beyond the individual with the addiction to examine the family dynamics that may, often unintentionally, enable the substance use to continue. These enabling behaviors—such as making excuses, providing money, or shielding the person from consequences—are typically born from love and a desire to avoid conflict, but they ultimately allow the addiction to thrive.

The evolution of family therapy models reflects the broader shift in understanding addiction. Early approaches like the Johnson Model were highly confrontational, focusing solely on breaking the denial of the person with the addiction. Modern, more effective approaches are systemic, recognizing that the entire family has adapted to the addiction and that the system itself must be repaired. These models include:

- Systemic Family Therapy: Focuses on repairing the family system as a whole, teaching all members healthier communication and boundary-setting skills. It can be effective even if the person with the addiction is not initially present, as changing the family’s behavior removes the enabling structure that supports the addiction.

- Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT): A comprehensive model designed for adolescents with SUDs, involving the individual, family, school, and other community systems.

- Behavioral Family Therapy (BFT): Uses principles of positive reinforcement and skills training to improve individual behaviors and strengthen family relationships.

By engaging in therapy together, families can learn about the disease of addiction, restore broken relationships, and build a home environment that actively supports and sustains long-term recovery. This integrated approach, where biological stability from MAT creates a platform for psychological skills from CBT, all reinforced within a healing family system, represents the gold standard of comprehensive addiction care.

Section 4: The Power of Community: A Comparative Analysis of Peer Support Models

For many, the journey of long-term recovery is sustained not just by clinical interventions but by the profound power of community. Peer support groups offer a unique and invaluable form of help: the shared experience and mutual understanding of people who have walked the same path. These groups provide a free, accessible, and ongoing source of accountability, hope, and belonging. However, the landscape of peer support is no longer a monolith. A variety of models have emerged, each with a distinct philosophy and approach. Understanding these differences is key to finding a community where one can feel truly at home.

The growth of diverse non-12-step programs represents a significant and positive trend toward personalization in recovery. It is a direct response to the reality that the traditional 12-step model, while life-saving for millions, is not a perfect fit for everyone, particularly those who are secular or who resonate more with a scientific, self-empowering framework. This evolution has created a marketplace of ideas, empowering individuals to become active consumers of their own recovery and choose the pathway that best aligns with their personal beliefs, values, and psychological needs.

Despite their profound philosophical differences, it is crucial to recognize that all successful peer support models share the same core “active ingredients.” Research comparing various groups shows that universal mechanisms of change—such as gaining hope, learning coping skills, benefiting from the help of peers, and finding a sense of community—are rated as equally important across all models. This suggests that while the specific ideology provides the framework, the true engine of change is the human connection and shared purpose that these groups foster. The most important factor may not be

which group a person chooses, but that they choose one and engage with it consistently.

Table 4.1: Comparative Overview of Major Peer Support Models

| Feature | 12-Step Programs (AA/NA) | SMART Recovery | LifeRing Secular Recovery | Refuge Recovery |

| Core Philosophy | Surrender and acceptance of powerlessness over addiction. | Self-empowerment through cognitive skills and self-reliance. | Self-empowerment through the “Sober Self”; personal responsibility. | Freedom from suffering through Buddhist principles of mindfulness and compassion. |

| View of Addiction | A threefold disease: physical, mental, and spiritual. | A maladaptive, self-destructive, and learned behavior; not a disease. | A disease of the body, but recovery is a matter of personal choice and effort. | Suffering caused by repetitive craving (“thirst”). |

| Role of “Higher Power” | Central; members surrender their will to a “higher power of their understanding”. | Secular; no mention of a higher power. Focus is on internal power. | Secular; religious/spiritual beliefs are a private matter and not part of the meeting. | Non-theistic; based on Buddhist philosophy, not a deity. Refuge is in awakening, truth, and community. |

| Key Program/Tools | The 12 Steps and the 12 Traditions; sponsorship. | The 4-Point Program® and a “toolbox” of cognitive-behavioral techniques. | The “3-S” Philosophy (Sobriety, Secularity, Self-Empowerment); designing one’s own program. | The Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path; meditation and inventory work. |

| Stance on Labels | Members typically identify as an “alcoholic” or “addict”. | Avoids labels like “addict” or “alcoholic” as they can be stigmatizing and unhelpful. | Does not use labels; focuses on the person, not the addiction. | Focuses on the shared human experience of suffering, not labels. |

| Approach to Relapse | Often viewed as a spiritual setback requiring a recommitment to the program. | A learning opportunity; not seen as a necessary part of recovery but a possibility. | A learning experience; members are not admonished for relapsing. | A return to suffering, addressed by re-engaging with the path and practices. |

4.1 The Great Divide: Surrender vs. Self-Reliance

The most fundamental philosophical difference that separates peer support models is the concept of personal power.

- The Surrender Model: At the core of 12-Step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous is the First Step: “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.” This philosophy posits that addiction is a disease so powerful that individual willpower is insufficient to overcome it. Recovery, therefore, requires a profound act of surrender—giving up the illusion of control and turning one’s will and life over to the care of a “higher power”. For many, this concept is a source of immense relief, freeing them from the crushing burden of trying and failing to control their addiction on their own.

- The Self-Reliance Model: In direct contrast, non-12-Step programs are built on a foundation of self-empowerment and personal responsibility. They believe that individuals possess the inherent power and capacity to control their own addictive behaviors. These programs focus on providing members with the psychological tools and strategies needed to build and strengthen their own internal resources for change. For individuals who are secular, agnostic, or who find the concept of powerlessness to be disempowering, this approach offers an alternative pathway to recovery.

4.2 12-Step Programs: Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) & Narcotics Anonymous (NA)

Founded in 1935, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is the original and most widely known peer support program for addiction. Narcotics Anonymous (NA) and dozens of other fellowships (e.g., Cocaine Anonymous, Gamblers Anonymous) are based on its principles. These programs are not formal therapy but function as self-help organizations guided by the 12 Steps and 12 Traditions.

The 12 Steps outline a spiritual program of action designed to bring about a “spiritual awakening” or personality change sufficient to overcome addiction. Key tenets include admitting powerlessness, turning to a higher power, making a moral inventory, making amends for past harms, and carrying the message to others. Sponsorship, where an experienced member guides a newcomer through the steps, is a cornerstone of the program. While often viewed as having religious undertones, the program encourages members to define their own “higher power,” which can be anything from a traditional God to the group itself or a spiritual principle. Despite limited formal research, numerous studies have shown that regular attendance at AA meetings is associated with significantly higher rates of abstinence, making it a highly effective and cost-effective pathway for many.

4.3 SMART Recovery: Self-Management and Recovery Training

SMART Recovery (Self-Management and Recovery Training) is the leading science-based, secular alternative to 12-Step programs. Founded on the principles of self-empowerment and self-reliance, SMART teaches participants how to control their addictive behaviors by focusing on their underlying thoughts and feelings. The program is grounded in evidence-based therapeutic techniques, primarily Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Motivational Interviewing (MI).

Instead of steps, SMART is built around a 4-Point Program®, which participants can work on in any order based on their needs:

- Build and Maintain Motivation

- Cope with Urges

- Manage Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

- Live a Balanced Life

Meetings are led by trained facilitators and focus on practicing practical tools and strategies from the SMART Recovery Handbook. SMART fundamentally differs from AA in several ways: it does not use a higher power, it avoids labels like “addict,” and it views recovery as a process one can eventually “graduate” from by mastering self-management skills, rather than a lifelong identity. It is open to people with any type of substance or behavioral addiction and, in its most recent edition, fully embraces a harm reduction perspective, allowing members to set their own goals, which may include moderation or abstinence.

4.4 LifeRing Secular Recovery: Empowering Your Sober Self

LifeRing is another prominent secular recovery organization that offers an alternative to spiritually-based programs. Its philosophy is captured in its motto, “empower your sober self,” and is based on the “3-S” principles:

- Sobriety: A commitment to complete abstinence from alcohol and non-prescribed drugs.

- Secularity: A focus on human efforts, where religious or spiritual beliefs are a private matter not discussed in meetings.

- Self-Empowerment: The belief that each individual has an inner “Sober Self” and a conflicting “Addict Self,” and that recovery is the process of strengthening the Sober Self.

LifeRing meetings are typically informal, cross-talk-based discussions where members share practical experiences and offer each other encouragement and support. Unlike the structured programs of AA or SMART, LifeRing encourages each member to design their own unique and personal recovery program. It does not use sponsors, but emphasizes the power of positive peer support to reinforce the sober self. LifeRing offers a flexible, humanist, and less-structured option for those seeking a secular community.

4.5 Refuge Recovery: A Buddhist Path to Freedom

Refuge Recovery offers a unique pathway for those who seek a spiritual framework for recovery that is not based on theism. It is a mindfulness-based program grounded in the core teachings of Buddhism. The program frames addiction as a form of suffering caused by repetitive craving, which the Buddha called “uncontrollable thirst”.

The path to healing in Refuge Recovery is through the practice of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, a set of principles for living an ethical and mindful life. Meditation is a cornerstone of the practice, used to cultivate awareness, wisdom, and compassion. Instead of surrendering to a higher power, members are invited to “take refuge” in three things: the Buddha (the potential for awakening within all beings), the Dharma (the truth of the teachings), and the Sangha (the community of fellow practitioners). Meetings involve guided meditations, readings from the Refuge Recovery book, and group sharing. This approach provides a structured, spiritual, and contemplative path to recovery that resonates with those drawn to Eastern philosophy and mindfulness practice.

Section 5: Co-occurring Disorders: Addressing the Complete Picture

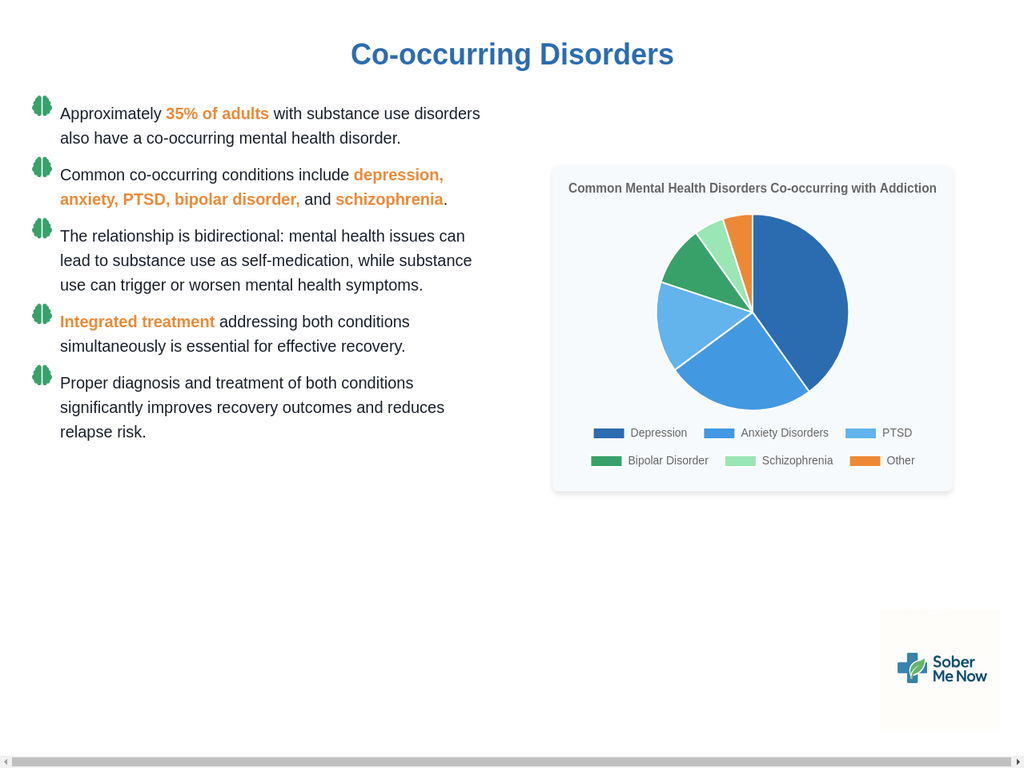

The journey of addiction recovery is rarely a simple matter of addressing substance use alone. More often than not, addiction is deeply intertwined with other mental health conditions. This overlap, known as a co-occurring disorder or dual diagnosis, is so common that it should be considered the rule rather than the exception. Acknowledging and treating these co-occurring conditions simultaneously is not just beneficial; it is essential for achieving stable, long-term wellness. An approach that ignores one condition while treating the other is addressing only half the problem and is likely doomed to fail.

The high prevalence of co-occurring disorders means that any effective addiction treatment program must also be a competent mental health program, and vice versa. This reality has driven a necessary and powerful shift in the healthcare field, breaking down the artificial silos that once separated addiction treatment from mental healthcare. The rise of integrated treatment models represents a maturation of the field, moving toward a truly holistic, person-centered approach that recognizes you cannot treat the brain in pieces. It provides a clear standard for quality care, empowering individuals and families to advocate for a comprehensive approach that addresses the complete picture of their health.

5.1 The Rule, Not the Exception: The Prevalence of Co-occurrence

The statistics on co-occurring disorders are stark and consistent. A large percentage of individuals with a substance use disorder (SUD) also have at least one other mental health disorder, and a significant portion of those with a mental health disorder also have an SUD. For example, the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 35% of U.S. adults with any mental disorder also had an SUD.

The most common mental health conditions that co-occur with addiction include:

- Mood Disorders: Such as Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder. As many as 80% of individuals with alcoholism experience depressive symptoms at some point, and 30% meet the full criteria for major depression.

- Anxiety Disorders: Including Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, and Social Anxiety Disorder.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Trauma is a significant risk factor for both addiction and other mental health issues.

- Personality Disorders: Such as Borderline Personality Disorder and Antisocial Personality Disorder.

This overlap is not a coincidence. It stems from a complex, intertwined relationship between the two types of conditions. For anyone struggling with both addiction and a mental health challenge, this data should be validating. It means they are not alone or uniquely flawed; their experience is, in fact, the norm in the world of recovery.

5.2 The Chicken and the Egg: Unraveling the Connection

The relationship between addiction and other mental disorders is complex and bidirectional, meaning each can influence and worsen the other. There is no single pathway, but several theories help explain the connection :

- The Self-Medication Hypothesis: This is one of the most common explanations. Individuals may use alcohol or drugs to cope with or numb the painful symptoms of an untreated mental illness. Someone with social anxiety might drink to feel more comfortable in social situations, or someone with depression might use stimulants to combat fatigue and low mood. While this may provide temporary relief, it almost always worsens the underlying condition in the long run.

- Shared Risk Factors: Often, both conditions stem from common underlying vulnerabilities. These can include genetic predispositions, environmental factors like poverty or social isolation, and exposure to stress or trauma, especially in childhood. These shared roots can set the stage for both an SUD and another mental disorder to develop.

- Substance-Induced Brain Changes: The use of drugs and alcohol can cause profound changes in brain structure and function. These changes can occur in the very same brain circuits that are disrupted in other mental disorders, potentially triggering the onset of a latent condition or exacerbating existing symptoms. For example, chronic cannabis use has been linked to an earlier onset of psychosis in vulnerable individuals.

This intricate web of influence creates a vicious cycle. The mental health symptoms drive the substance use, and the substance use worsens the mental health symptoms. Untangling this cycle requires a treatment approach that can address both threads simultaneously.

5.3 The Fallacy of Sequential Treatment: Why Integrated Care is Essential

For many years, addiction and mental health were treated in separate systems. A person was often told they had to get sober before they could get help for their depression, or that their anxiety had to be under control before they could address their drinking. This is known as sequential treatment, and it has been proven to be largely ineffective.

Treating only one co-occurring disorder while ignoring the other is a recipe for failure. The untreated condition remains a powerful driver of relapse. The modern, evidence-based standard of care is

integrated treatment, an approach where an individual receives care for both their SUD and their mental health disorder at the same time, preferably from the same team of professionals or through closely coordinated services.

The principles of integrated treatment include:

- Simultaneous Treatment: Addressing both conditions concurrently in a cohesive treatment plan.

- Person-Centered Care: Tailoring the plan to the individual’s unique needs, goals, and challenges.

- Collaborative Team Approach: A multidisciplinary team with expertise in both mental health and addiction works together to provide unified care.

- Continuity of Care: A long-term approach that provides ongoing support as the individual’s needs evolve.

The benefits of this approach are well-documented. Integrated treatment leads to better clinical outcomes, including reduced symptoms for both disorders, higher rates of treatment engagement and retention, reduced stigma, and an overall improvement in quality of life. It is the most effective and compassionate way to help individuals with co-occurring disorders achieve lasting recovery.

5.4 Beyond Mental Health: Co-occurring Physical Conditions

The impact of addiction extends beyond mental health to the entire body. Substance use disorders frequently co-occur with a range of serious physical health conditions that must also be addressed as part of a comprehensive recovery plan. These include:

- Infectious Diseases: Injection drug use is a major risk factor for the transmission of blood-borne viruses like HIV and hepatitis C. Furthermore, substance use can impair judgment, leading to unsafe sexual practices that also increase the risk of transmission.

- Heart Disease: The use of numerous substances, including alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin, is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular problems.

- Chronic Pain: There is a strong and complex link between chronic pain and OUD. Many individuals develop an OUD after being prescribed opioids for pain, and nearly half of those with OUD also suffer from chronic pain.

- Cancer: Smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer, and alcohol use is strongly linked to several other types of cancer.

True recovery requires a “whole person” approach that integrates medical care to address these physical health issues alongside the psychological and behavioral aspects of addiction.

Section 6: Holistic Well-being: Integrating Mind, Body, and Spirit in Recovery

While clinical interventions and peer support form the structural beams of recovery, a truly robust and resilient sobriety is often fortified by holistic practices that integrate the mind, body, and spirit. These strategies are not merely “complementary” or “alternative”; they are powerful, evidence-supported interventions that directly target the same neurobiological systems affected by addiction. Nutrition, exercise, and mindfulness are not just about feeling good—they are forms of self-administered brain therapy that provide the raw materials for healing, regulate mood and stress, and help build a life that is fundamentally healthier and more fulfilling.

A sophisticated understanding of these practices also requires a note of caution. Because activities like exercise powerfully activate the brain’s reward system, there is a potential for “addiction transfer,” where a healthy behavior becomes a new compulsion. This is more likely to occur in individuals who have struggled with other addictions. Therefore, the goal is to use these tools to heal and balance the reward system, not to substitute one compulsive pattern for another. A mindful approach, emphasizing balance and moderation, is key to harnessing the benefits of these practices without falling into a new trap.

6.1 The Body’s Foundation: The Critical Role of Nutrition

Chronic substance use wreaks havoc on the body’s nutritional state. It often leads to irregular eating, poor food choices, and impaired absorption of nutrients, resulting in widespread deficiencies that can exacerbate the very symptoms people are trying to escape: mood instability, anxiety, poor sleep, and low energy. Proper nutrition is therefore a critical component of recovery, as it provides the brain and body with the essential building blocks needed to repair damage and restore chemical balance.

A balanced diet focusing on whole foods—complex carbohydrates, lean proteins, healthy fats, fruits, and vegetables—is essential. Certain nutrients are particularly important for the recovering brain :

- Amino Acids for Neurotransmitter Production: Neurotransmitters are the brain’s chemical messengers that regulate mood and motivation. Addiction severely depletes them.

- Tyrosine: This amino acid is a precursor to dopamine, the “feel-good” neurotransmitter. Restoring dopamine levels is crucial for combating anhedonia and depression. Tyrosine is found in protein-rich foods like chicken, fish, dairy, nuts, and beans.

- L-Glutamine: This is a precursor to GABA, the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, which promotes calm and relaxation. L-glutamine can help regulate stress responses and is found in beef, fish, poultry, and beans.

- Antioxidants to Reduce Brain Stress: Substance use creates significant oxidative stress in the brain, a condition linked to depression and anxiety. Antioxidants combat this damage. They are abundant in colorful fruits and vegetables like berries, grapes, tomatoes, and broccoli.

- Complex Carbohydrates and Healthy Fats: Eating regular, balanced meals that include complex carbohydrates (like whole grains and legumes) and healthy fats (like olive oil and nuts) helps to stabilize blood sugar. This is crucial for preventing mood swings and cravings that are often triggered by hunger and low blood sugar.

Focusing on nutrition is a tangible and empowering way for an individual to actively participate in their own healing process, literally rebuilding their brain from the inside out.

6.2 The Power of Movement: Exercise as Medicine

Regular physical activity is one of the most powerful and accessible tools in the recovery arsenal. Its benefits are profound because exercise works on the very same neurochemical pathways that are hijacked by addiction. When you engage in physical activity, your brain releases endorphins, dopamine, and serotonin—the same chemicals that produce feelings of pleasure, well-being, and reward—but in a healthy, balanced, and non-addictive way.

The benefits of incorporating a regular exercise routine into recovery are extensive and well-documented :

- Curbs Cravings and Reduces Use: Studies show that exercise can directly reduce the urge to use substances and increase the number of abstinent days. Even as little as five minutes of activity can provide protection against a craving.

- Relieves Stress and Boosts Mood: Exercise is a natural antidepressant and anxiolytic. It helps to regulate the brain’s stress response systems and provides a reliable mood boost, which is critical for managing the emotional volatility of early recovery.

- Provides Structure and Routine: Scheduling workouts helps to structure the day, filling the empty time left by the absence of substance use and minimizing the temptation to fall back into old patterns.

- Improves Sleep: Insomnia is a common and distressing symptom of withdrawal and PAWS. Regular exercise is proven to improve sleep quality, which is vital for both physical and mental restoration.

- Boosts Self-Esteem: Accomplishing fitness goals, no matter how small, builds confidence and reinforces a positive self-image. It demonstrates to the individual that they are capable of doing hard things and taking care of themselves.

The best type of exercise is the one a person enjoys and will do consistently. Options range from aerobic activities like walking, running, swimming, and dancing to strength training, yoga, hiking, and team sports.

6.3 The Quiet Mind: Mindfulness, Meditation, and Stress Management

If addiction is often a flight from uncomfortable feelings, then mindfulness is the practice of learning to stay. Mindfulness is the art of paying attention to the present moment—to your thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations—with curiosity and without judgment. It is a foundational skill for stress management and emotional regulation, directly addressing the internal triggers that so often lead to relapse.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs) are now a formal component of many evidence-based treatment programs because they are so effective at altering how an individual responds to urges and cravings. The practice encourages a separation between a thought and an action. Instead of being compelled to act on an intrusive thought about using, an individual learns to simply observe it, accept its presence, and let it go without being controlled by it.

Key mindfulness techniques include :

- Mindful Breathing: This is the anchor of most mindfulness practices. By focusing on the physical sensation of the breath entering and leaving the body, you can ground yourself in the present moment and calm a racing mind.

- Meditation: This is the formal practice of cultivating mindfulness. It can involve sitting meditation, walking meditation, or guided meditations that focus on developing qualities like self-compassion.

- Body Scan: This practice involves systematically bringing your attention to different parts of your body, noticing any sensations without judgment. It is a powerful tool for grounding and reducing anxiety.

By regularly practicing mindfulness, individuals develop the capacity to tolerate distress, regulate their emotions, and make conscious choices rather than reacting on autopilot. This is a true superpower in recovery.

6.4 The Spirit of Recovery: Holistic and Expressive Therapies

Holistic therapy approaches recovery from the perspective of the “whole person,” seeking to heal and integrate the mind, body, and spirit. This often includes the nutritional, physical, and mindfulness practices described above, but also extends to therapies that nurture the spiritual and creative dimensions of a person’s being.

Expressive arts therapies—such as art, music, dance, and writing—can be particularly powerful in recovery. They provide a non-verbal outlet for processing complex emotions, especially those related to trauma, that may be difficult to access or articulate through traditional talk therapy. Engaging in creative activities can help individuals explore their inner world, process difficult feelings in a safe way, and build a stronger, more authentic sense of self. Other holistic practices commonly used in recovery include:

- Yoga and Tai Chi: These practices combine physical movement, breathwork, and meditation to improve the connection between mind and body, reduce stress, and enhance self-awareness.

- Breathwork: This involves the conscious control of breathing patterns as a therapeutic tool to release tension, process emotions, and manage cravings.

- Recreational Therapy: Engaging in structured recreational activities, from hiking to team sports, can provide a sense of purpose and fulfillment, and help individuals learn new skills for a healthy, sober lifestyle.

These therapies validate the importance of creativity, self-expression, and finding new sources of meaning and purpose. For many, recovery is not just about abstaining from a substance; it is a profound journey of self-discovery, and these practices provide a structured and supportive way to facilitate that journey.

Section 7: Rebuilding and Thriving in Sobriety

Overcoming an active addiction is a monumental achievement, but it is only the first step. The ultimate goal of recovery is not simply to survive without a substance but to build a life that is so rich, meaningful, and fulfilling that the old way of life no longer holds any appeal. This final, crucial phase of the journey shifts the focus from stopping a behavior to starting a new life. It involves the practical, day-to-day work of constructing a pro-recovery environment, forging a new sober identity, and rediscovering joy and purpose.

This process of life-rebuilding is not separate from the internal work of therapy; the two are deeply synergistic. The internal skills learned in therapy, such as managing emotions and challenging negative thoughts, are practiced and solidified in the real-world arenas of new jobs, hobbies, and relationships. In turn, the positive experiences and connections gained from these external activities provide powerful evidence that a sober life is not only possible but preferable, reinforcing the therapeutic work and creating a positive feedback loop of sustainable change.

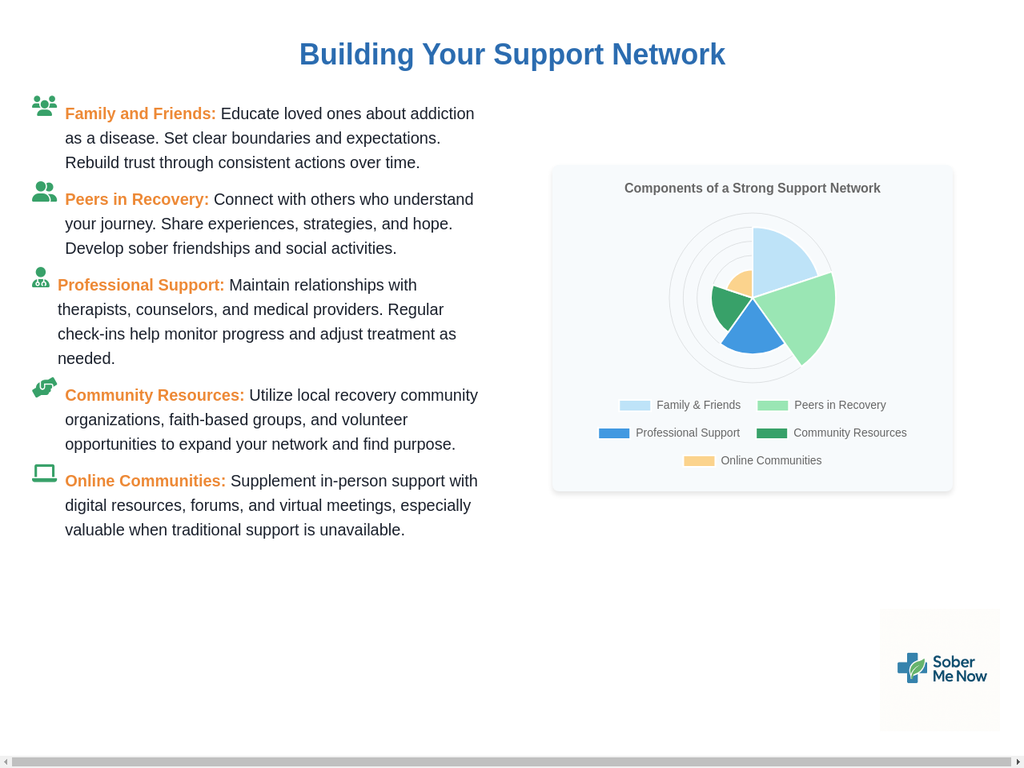

7.1 Building Your “Sober Squad”: The Power of Social Support

Recovery is not a journey meant to be taken alone. One of the most critical tasks in building a new life is to intentionally construct a strong, supportive social network. This “sober squad” is a vital buffer against the stress, loneliness, and triggers of daily life and a cornerstone of long-term success.

This network should be multi-layered and can include:

- Supportive Family and Friends: Individuals who understand, respect, and actively encourage your sobriety goals. This may require open communication about your needs and setting clear boundaries.

- Peers in Recovery: People from support groups like AA, SMART Recovery, or others who offer a unique level of empathy because they share the same lived experience. They provide accountability, motivation, and a powerful sense of not being alone.

- Sponsors or Mentors: An experienced individual from a support group who can provide guidance and one-on-one support.

- Professionals: Ongoing connection with a therapist, counselor, or doctor provides a foundation of professional support.

Actively building this network involves participating in support group meetings, engaging in sober community activities, and being willing to be vulnerable and ask for help. This sense of community and belonging is a powerful antidote to the isolation that so often fuels addiction.

7.2 Finding New Joys: Rediscovering Hobbies and Sober Activities

Active addiction consumes an enormous amount of time, energy, and mental space. In early recovery, the resulting vacuum can feel vast and daunting. Proactively filling this time with healthy, enjoyable, and engaging activities is not just a distraction; it is the process of rewiring the brain’s reward system to find pleasure in sober pursuits.

This is a journey of rediscovery and exploration. It might involve revisiting old hobbies that were abandoned during addiction or being brave enough to try something entirely new. The possibilities are endless and deeply personal, but can include :

- Creative Outlets: Painting, playing a musical instrument, writing, journaling, or photography can provide powerful channels for emotional expression and a sense of accomplishment.

- Physical Activities: Joining a sober sports league, taking up hiking, running, cycling, or rock climbing not only provides the neurochemical benefits of exercise but also builds camaraderie and trust.

- Skill-Building: Learning a new skill like cooking, gardening, a new language, or a DIY home improvement project fosters self-esteem and cognitive renewal.

- Sober Socializing: Intentionally creating new social norms is key. This can involve hosting game nights that don’t involve drinking, exploring coffee shops, attending art and music festivals without substances, or joining book clubs.

By engaging in these activities, an individual is not just passing time; they are actively building a new identity—as a musician, an athlete, a chef, a volunteer—that is richer and more authentic than the one they left behind.

7.3 A Life of Purpose: Setting Meaningful Goals

Addiction often forces life into a narrow, repetitive loop focused on the next use, overshadowing larger ambitions and dreams. Sobriety opens up the space to rediscover a sense of purpose and to set meaningful goals that provide direction and motivation. These goals shift the focus of recovery from one of

avoidance (not using) to one of aspiration (building a better future).

These goals can be in any life domain and should be personally meaningful:

- Career/Education: Going back to school, earning a certification, starting a new career, or advancing in a current one.

- Relationships: Mending relationships that were damaged by addiction, being a more present parent or partner, or building new, healthy friendships.

- Personal Growth: Working on a specific character trait, developing a spiritual practice, or learning a new skill.

- Contribution: Volunteering time to a cause you care about, perhaps even helping others who are new to recovery.

Setting clear, achievable goals provides a roadmap for the future and generates a sense of accomplishment with each milestone reached, reinforcing the value and rewards of a sober life.

7.4 The Stability of Structure: Creating a Pro-Recovery Routine

In the often-chaotic emotional landscape of early recovery, a structured daily routine provides an essential anchor of stability and predictability. A routine minimizes decision fatigue—the mental exhaustion that comes from constantly having to make choices—and reduces the amount of unstructured time where boredom, loneliness, and temptation are most likely to creep in.

A pro-recovery routine is a conscious plan for the day that prioritizes healthy habits. It might include:

- Consistent wake-up and sleep times to support healthy sleep hygiene.

- Scheduled time for work or school.

- Planned, regular meals to maintain stable blood sugar and energy.

- A dedicated slot for exercise or physical activity.

- Time for mindfulness, meditation, or journaling.

- Scheduled attendance at support group meetings.

- Time for hobbies and relaxation.

This structure provides a sense of control and purpose, creating a reliable framework that supports sobriety and helps to ground the individual as they navigate the challenges of recovery.

7.5 Celebrating the Wins: Acknowledging Your Progress

The path of recovery can feel long and arduous, and it is easy to focus on the struggles. For this reason, it is vital to consciously pause and celebrate the victories, no matter how small. Acknowledging milestones—one day, one week, one month, one year of sobriety—is a powerful way to build self-esteem and reinforce motivation.

Celebration doesn’t have to be extravagant. It can be a simple reward, like treating yourself to a nice meal, buying a new book, or taking a day trip. The act of celebration serves several important functions:

- It counteracts the negative self-talk and shame that are often remnants of addiction.

- It provides tangible proof of progress, reminding you how far you have come.

- It breaks the long journey down into manageable, rewarding steps.

By taking the time to honor your achievements, you are actively nurturing a positive relationship with yourself and reinforcing the belief that you are worthy and capable of a healthy, sober life.

Section 8: Directory of Key National Resources

Navigating the path to recovery can be overwhelming, but you do not have to do it alone. A wealth of reliable, confidential, and often free resources are available to provide immediate help, treatment referrals, and evidence-based information for individuals and families affected by substance use and mental health disorders.

8.1 Immediate Help & Treatment Referral

- SAMHSA National Helpline:

- Phone: 1-800-662-HELP (4357)

- Description: A 24/7, free, and confidential treatment referral and information service for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders. Service is available in English and Spanish.

- FindTreatment.gov:

- Website: https://www.findtreatment.gov/

- Description: A confidential and anonymous online tool managed by SAMHSA that allows you to search for substance use and mental health treatment facilities anywhere in the United States and its territories.

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline:

- Phone: Call or text 988

- Description: Provides 24/7, free, and confidential support for people in distress, as well as prevention and crisis resources for you or your loved ones.

8.2 Government & Research Organizations

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA):

- Website: https://www.samhsa.gov/

- Description: The leading U.S. federal agency for advancing the behavioral health of the nation. SAMHSA’s mission is to reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on America’s communities. The agency provides grants, manages data collection, and disseminates evidence-based practice toolkits for professionals and the public.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA):

- Website: https://www.nida.nih.gov/

- Description: A part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), NIDA is the lead federal agency supporting scientific research on drug use and its consequences. The website is an authoritative source of information on the science of addiction, treatment, and prevention for patients, families, and clinicians.

8.3 Mental Health & Family Support

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI):

- Website: https://www.nami.org/

- Description: The nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization, dedicated to building better lives for the millions of Americans affected by mental illness. NAMI provides advocacy, education, support, and public awareness so that all individuals and families affected by mental illness can build better lives. This is a crucial resource for those dealing with co-occurring disorders.

- The Jed Foundation (JED):

- Website: https://www.jedfoundation.org/

- Description: A leading non-profit organization that protects emotional health and prevents suicide for teens and young adults in the United States. JED partners with high schools and colleges to strengthen their mental health, substance misuse, and suicide prevention programs and systems.

Featured Articles: